Roundworms are the internal worms that cause the most problems for sheep, but there are other internal worms that animals encounter.

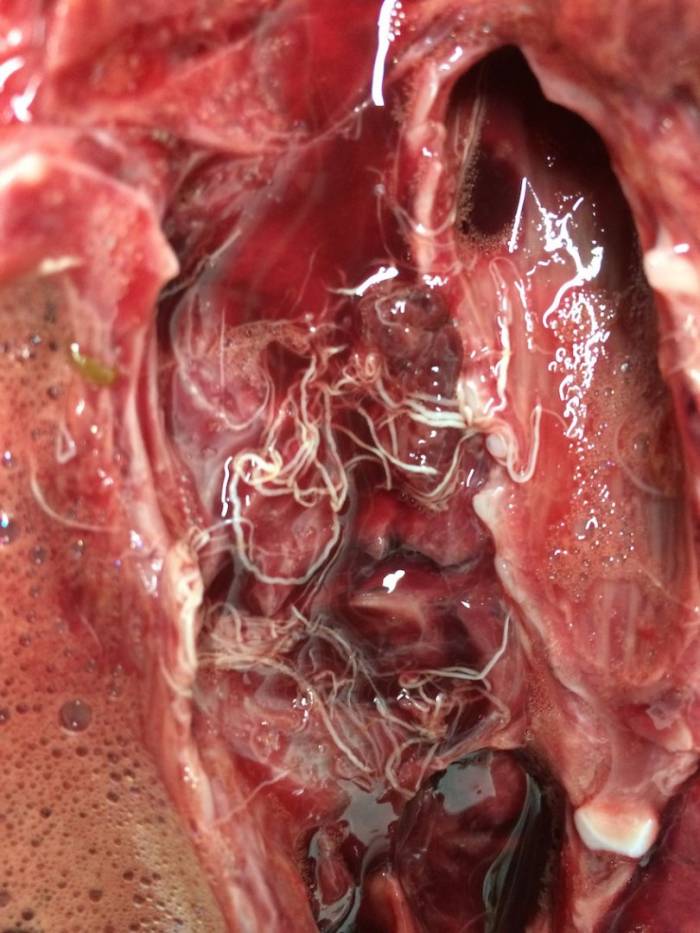

Disease in sheep due to lungworm is usually less severe than that seen in cattle. The most important lungworm species when it comes to sheep is Dictyocaulus filaria. The lifecycle of this lungworm is similar to that of a roundworm, in that eggs are passed out in faeces. When ingested by a naïve sheep, the lungworm eggs mature while penetrating the intestinal mucosa and passing to the lymph nodes, travelling via the lymph and the blood to the lungs. The lungworm moults in the bronchioles and the young adults move up the bronchi, causing laboured breathing and coughing in grazing animals, usually in the autumn. It is important to speak to your vet if your flock is demonstrating these symptoms, to confirm if lungworm is the culprit.

There are also some metastrongylid lungworm species that occur in sheep, picked up when animals ingest an infected slug or snail. These usually only cause a mild infection that is not normally a problem – although heavy infections may cause bronchopneumonia and damage lung tissue.

Despite being a common parasite of the intestines of sheep, with segments occasionally seen in sheep faeces, Moniezia tapeworm infections are generally symptomless – although a lack of thrift or diarrhoea is not unheard of.

Other, less common types of tapeworm can cause cysts in sheep. If formed on the brain, these can lead to the condition known as ‘sturdy’ or ‘grid’ (when sheep become uncoordinated, paralysed and/or lose vision). If formed elsewhere, these can result in local condemnation of affected organs or total carcase condemnation at the abattoir. The economic impact of condemnations caused by tapeworms can mount up, and very heavy infection levels of some tapeworms can kill young lambs, so speak to your vet about any abattoir feedback you receive.

More on other internal parasites in the SCOPS Technical Manual. Chapter 3.5.